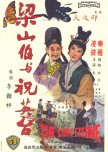

The Love Eterne illustrates the power of simple, timeless storytelling to resonate. The narrative (based on the Chinese legend "The Butterfly Lovers") is straight-forward: a young girl disguises herself as a man to attend college and falls in love with her "sworn brother" (i.e. blood brother/best friend), only to face familial obstacles when they later want to marry. Li Han-Hsiang’s production is exquisite and working in gorgeous synergy: elaborate and colorful sets and costumes, scenic widescreen photography, and playful, romantic musical numbers in the style of Huangmei opera (the 十八相送/“Eighteen Miles Away” sequence is truly an all-timer). There’s never a moment in which the narrative deviates from an expected development, and yet it’s so sincerely portrayed and opulently mounted that any concern for overfamiliarity were gently charmed away.

The most subversive element of the film is that both leads are played by women, Betty Loh Ti (with poignant vocals dubbed by Tsin Ting) as the girl disguised as a boy and Ivy Ling Po as the boy she falls in love with. Both are magnificent, so convincing as the yearning heterosexual couple that the casting of two women seems an inextricable part of the story’s message about the role of women in society despite the fact that this is based on a truly heterosexual ancient legend (from roughly 266–420 AD). I have to imagine, or at least hope, that Chinese queer cultural critics have written some fascinating studies of this film, particularly because it seems to be widely considered a populist Chinese classic.

The story continues on irrespective of deeper implications, building to its inevitable, operatic climax bursting with raw emotion (here is where Loh truly shines). The ending is poignant and wistful, and I understood why this story had lasted all these years.

The most subversive element of the film is that both leads are played by women, Betty Loh Ti (with poignant vocals dubbed by Tsin Ting) as the girl disguised as a boy and Ivy Ling Po as the boy she falls in love with. Both are magnificent, so convincing as the yearning heterosexual couple that the casting of two women seems an inextricable part of the story’s message about the role of women in society despite the fact that this is based on a truly heterosexual ancient legend (from roughly 266–420 AD). I have to imagine, or at least hope, that Chinese queer cultural critics have written some fascinating studies of this film, particularly because it seems to be widely considered a populist Chinese classic.

The story continues on irrespective of deeper implications, building to its inevitable, operatic climax bursting with raw emotion (here is where Loh truly shines). The ending is poignant and wistful, and I understood why this story had lasted all these years.

Esta resenha foi útil para você?