¡MyDramaList necesita escritores y editores!

¡MyDramaList necesita escritores y editores!

“Art and literature can make their way into places where politics cannot, and win what cannot be won with weaponry.” - Kim Jong Il

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, also known as North Korea, is the forgotten Korea. When we think about Korea, we only think about its rich, prosperous, and democratic neighbour, the Republic of Korea (or South Korea). North Korea is not only forgotten but also unknown, apart from the world headlines about nuclear weapons and ridiculous internet memes. Nevertheless, beyond dictatorship and widespread violations of human rights, there are ordinary citizens, people just like us, with their personal problems, worries, and moments of joy, who just want to carry on and be happy.

Most of us certainly do not think about or even wonder how these people entertain themselves. What kind of dramas do they watch? Do they go to the cinema? Do they have access to physical media at all? Are North Korean dramas similar to the K-dramas we enjoy? This article aims to explore the essence behind North Korean dramas and movies, the factors which make them so unique as well as contextually ambiguous to modern viewers. So, get your passports ready because we are heading to the Hermit Kingdom (or Best Korea, as known to devoted socialists).

Propaganda and Ideology |

No Motherland Without You is one of the most famous North Korean songs. The repeated choir is "We cannot live without you! Our country cannot exist without you!” These lines perfectly define the essence of North Korean entertainment. There is no single North Korean drama or movie that does not mention the leader, the party or the official ideology in one way or another. Any other topics, such as romance or characters’ conflicts, are beneath the official line of propaganda.

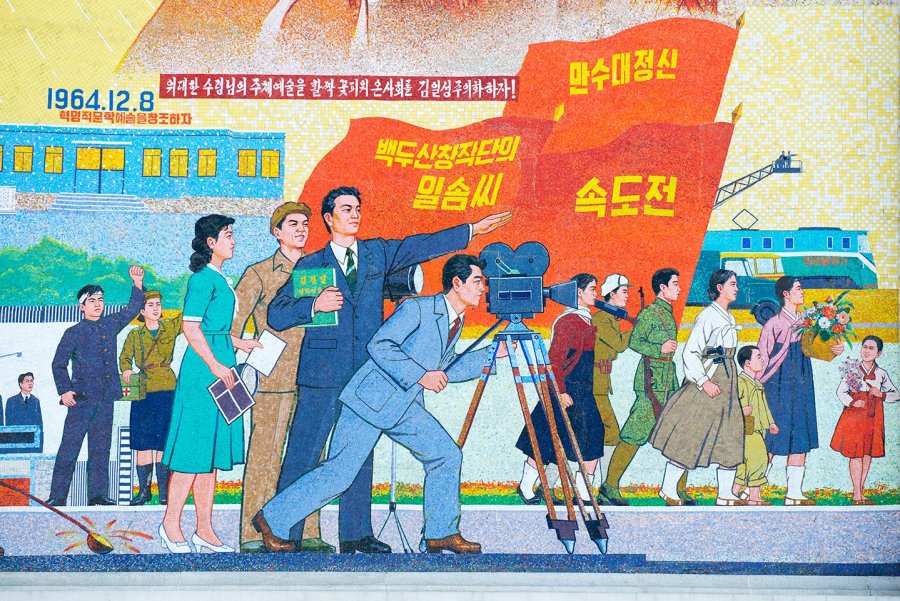

In consequence, dramas and movies are essential elements of North Korean propaganda since they uniquely convey the official ideology. After the division of the Korean peninsula, filmmakers in the North and the South entered the informal race to make the first picture about the liberation of their newly founded countries. The South Koreans did it first with Viva Freedom! (1946), whereas North Koreans released My Home Village in 1949, a movie which served as a template for the later DPRK productions to come.

Kim Il Sung and his son, Kim Jong Il, were two cinephiles who saw the potential in visual arts to propagate the socialist way of life. Movies, in particular, were meant to reflect the basics of Juche ideology; that is, the nation’s self-reliance in the spheres of politics, economy, belief systems, and national defence. In order to instil Kim Il Sung’s ideas into the viewers, movies often relied on the themes of martyrdom for the nation, colonial exploitation of Korea by the Japanese, and redemption in the face of the ultimate challenge. There was war, death, betrayal, and suffering. All of this had to be endured by the protagonists who were in the end saved by Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla army. What ensued later was the establishment of the perfect, happy society devoted to the Great Leader who looked after his dear subjects.

Kim Il Sung was relentlessly portrayed as the only true saviour of the Korean nation, not after the horrendous World War II, but after the 5000-year-long history of Korean peninsula filled with misery. As Johannes Schonherr writes in his academic paper: “Liberating it from the Japanese, driving out the feudal lords and eventually becoming the benevolent father of all Koreans. […] In return, the liberated people vowed to defend their country, race, and, above all, their endlessly beloved and revered leader” (source). This was the basic myth recycled in movies between the 1940s and the 1960s. The upright Korean people had to realise the potential of communism and take a stand against the Japanese oppressors.

Dramas |

The Nation and Destiny |

“Without watching ‘The Nation and Destiny,’ you cannot understand North Korean cinema and the North Korean soul!” - North Korean actor

Likewise, you can’t talk about North Korean dramas without mentioning The Nation and Destiny. It is the longest, most expensive and most notable North Korean drama ever. Projected to have 100 episodes (even though it only reached 62) and aired between 1992 and 2002, The Nation and Destiny aims to show that the Korean people "can live a glorious life only in the bosom of the Great Leader and socialist fatherland." (source) Kim Jong Il was personally involved in the production of this drama, that depicts the lives of different notable characters in recent Korean history, as well as the lives of workers, peasants and ordinary people across generations.

Among the aforementioned notable characters are Choe Deok Shin, a South Korean foreign minister who reportedly defected to North Korea with his wife; Isang Yun, a South Korean composer involved in the democratization of South Korea, who was kidnapped from West Germany by the KCIA in 1967; Choi Hong Hi, a South Korean army general who mastered taekwondo, went into exile in Canada and later moved to North Korea in 1979; and Ri In Mo, a North Korean guerrilla fighter who spent 34 years in a South Korean prison.

|  |

What is more important, The Nation and Destiny brought about an irreversible change in the North Korean propaganda that lives on today. Until then, the Republic was good because it was rich and prosperous (North Korea was, in fact, richer than its southern neighbour until the mid-1970s) thanks to general Kim Il Sung and the “superior” socialist system. However, after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, and the embracement of capitalism by former socialist countries, North Koreans acknowledged that the capitalist world, indeed, offered some things they desired and lacked.

Therefore, the message shifted to patriotism and unconditional love for the nation in spite of hardship*, while, at the same time, the North Korean public had to become indifferent to capitalism by gradual exposure. To achieve this goal, The Nation and Destiny did what no North Korean production had ever done before: shooting scenes in Western countries (France and Germany), featuring South Korean popular songs, and presenting a more realistic portrayal of the West.

The drama, however, did not have the desired effects on the North Korean people, who were, in turn, captivated by the depiction of capitalist affluence. One of the most striking examples is the depiction of South Korean prisons: when Ri In Mo goes into a hunger strike, this scene is shown as an instance of suffering in South Korean prisons. However, North Koreans concluded that food in South Korean prisons was so abundant that prisoners could go on hunger strike.

|  |

The most important message The Nation and Destiny conveys is one of forgiveness to those who repent. Repentance had always meant the acceptance of Kim Il Sung and the Juche ideology as well as acknowledgement of the DPRK as the only legitimate Korea. However, The Nation and Destiny shyly introduces a new concept of repentance: fighting for the reunification of the fatherland, transcending ideology, political views, and religious beliefs. Nevertheless, this apparent openness should not be taken as an open invitation to subversion: Kim Il Sung is still the leader of all Koreans, and acknowledgement of his leadership, as well as the superiority of the North Korean social system, is seen as a natural phase in being forgiven and accepted into the motherland.

All in all, no North Korean drama has ever gained the same recognition and popularity as The Nation and Destiny. It will remain in the hearts of North Koreans as the drama that opened a small window to the world for them.

NK-dramas |

North Korean dramas, or NK-dramas, are a relatively new occurrence. Their production began in the late 1970s when Kim Jong Il took charge of the country's propaganda efforts. Nevertheless, the focus was always put on cinema until the 1990s, when The Nation and Destiny was produced.

Nameless Heroes was the drama that started it all. Consisting of 20 episodes aired between 1978 and 1981, the drama tells the story of Yu Rim, a Korean expatriate in the UK who is ordered to proceed to Seoul and gather intelligence on the US Forces Korea. Initially, he only has three contacts in Seoul: Park Mu, the chief press officer for the South Korean Army; Janet O'Neill, the wife of a senior US intelligence official; and Lee Hong Shik, his handler.

Nameless Heroes is not only notable for being the first North Korean production of such type, but also for being the first North Korean production to cast real foreigners (four US soldiers who defected to North Korea in the 1960s) as actors. After Nameless Heroes, the production of dramas was put on hold and would not be resumed until a decade later.

|  |  |  |  |

Nowadays, there has been a surge in drama production in North Korea, unseen since the days of The Nation and Destiny. In addition, North Korean dramas have undergone a notable transformation as a consequence of the use of new equipment, modern filming techniques, enhanced photography and less ideologized screenplays, in a conspicuous effort to compete with South Korean dramas.

That does not mean, however, that NK-dramas are in any way like the K-dramas we love. The plot is still subjected to the official ideology, and there is a clear lack in variety of genres, characters and plots. Besides, unlike K-dramas, NK-dramas do not have a steady number of episodes, and the volume of production is low in comparison to that of the South Korean entertainment industry.

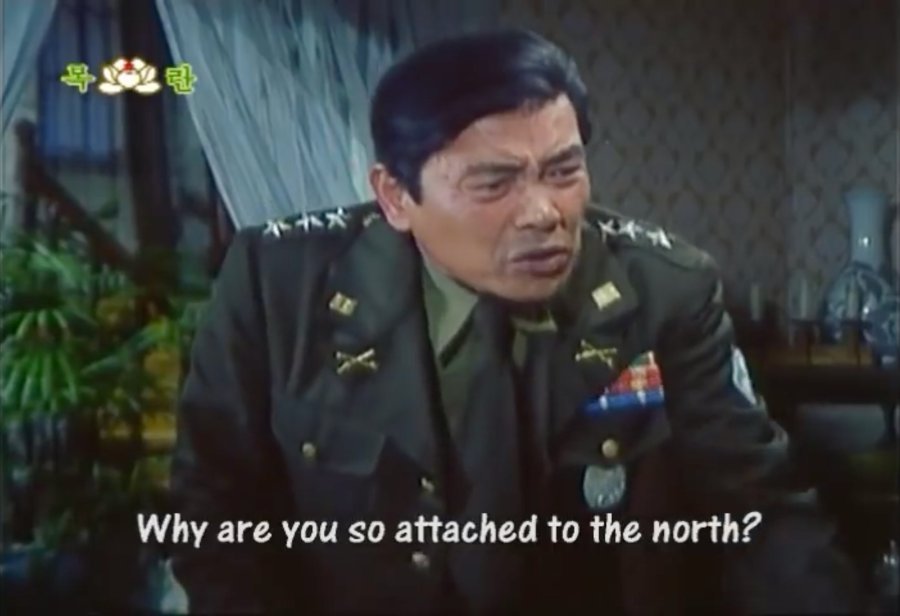

The drama that most notably embodies this recent transformation is Bullet-proof Wall. Aired in 2015, this 14-episode psychological thriller revolves around Japanese and US imperialists and Korean spies fighting a spy war in the shadows. Set in the 1940s, the story begins with Ok Chol and her brother wandering around Manchuria to find their father, who left home over a decade ago. When they finally find him, they are surprised to discover that he has now become a rich man. The father, however, funds and assists the Chosun People’s Revolutionary Army, the anti-Japanese guerrilla formed by Kim Il Sung, while pretending to support Japanese rule.

While the NK-drama world is not as wide and varied as the K-drama world, it still produces interesting and high-quality works that deserve the appreciation of viewers. NK-drama production is in full swing these days and, in some way, it reminds of the early stages of drama production in South Korea.

The Authors' Drama Recommendations |

| The Nation and Destiny (1992-2002) 민족과 운명 제 A 62-part epic tale based on the lives of notable Korean figures as well as ordinary workers, all struggling for the benefit of the Party. North Korean audiences were deeply captivated by the unconventional drama that realistically portrayed the Western world. |

(Unofficial cover) (Unofficial cover) | Nameless Heroes (1978-1981) 이름 없는 영웅들 The first North Korean drama ever, Nameless Heroes tells the tragic story of Yu Rim, a North Korean spy in Seoul after the liberation of Korea. The drama is notable for casting real foreigners as actors using four US military defectors. It was converted into colour in 2018. |

| Bullet-proof Wall (2015) 방탄벽 Set in the 1940s, this psychological thriller tells the story of Ok Chol and her rich father's fight against the Japanese occupiers of the Korean peninsula, and against the US and South Korean authorities after the division of the country. |

| Our Warm House (2004) 따뜻한 우리 집 This drama tells the story of the romance between Yong Jun and Ryon Hui, two doctors at the at Pyongyang Maternity Hospital. |

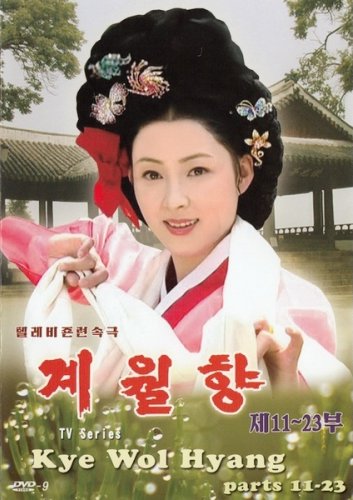

| Kye Wol Hyang (2011) 계월향 Historical drama set during the Imjin War in the 16th century. The drama tells the story of Kye Wol Hyang, a famous gisaeng in Pyongyang. During the Japanese invasion, Kye seduces and deceives Japanese general Konishi Yukinaga to kill him. |

Films |

Kim Jong Il: The Hollywood Producer |

At the beginning of the 1960s, Kim Jong Il was gradually entering the political sphere managed by his father. Contrary to Kim Il Sung, who was perceived as the nation’s hero, Kim Jong Il was an introvert raised in isolation. Instead of becoming a teamwork person, he took a liking to the arts, especially opera performances and movies. Allegedly, it is said that he accumulated over 15,000 movies on 35mm films from all over the world (source). Being one of the few people in the country allowed to watch foreign productions, he is said to have particularly enjoyed James Bond and Rambo franchises.

Kim Jong Il’s passion for movies landed him a supervising position in the Propaganda and Agitation Department in the 1960s. He quickly realised that the local productions were too formulaic and oversaturated with ideology. As the would-be leader described in a secretly recorded conversation:

“Why do all our films have the same ideological plots? There’s nothing new about them. Why are there so many crying scenes? […]. This isn’t a funeral, is it? We don’t have many films that get into film festivals. But in South Korea, they have better technology. They are like college students. We are just in nursery school. People here are so close-minded.” (source)

|  |

What is more, Kim Jong Il complained at uneducated directors and actors who were not trying because they knew they’d get paid anyway.

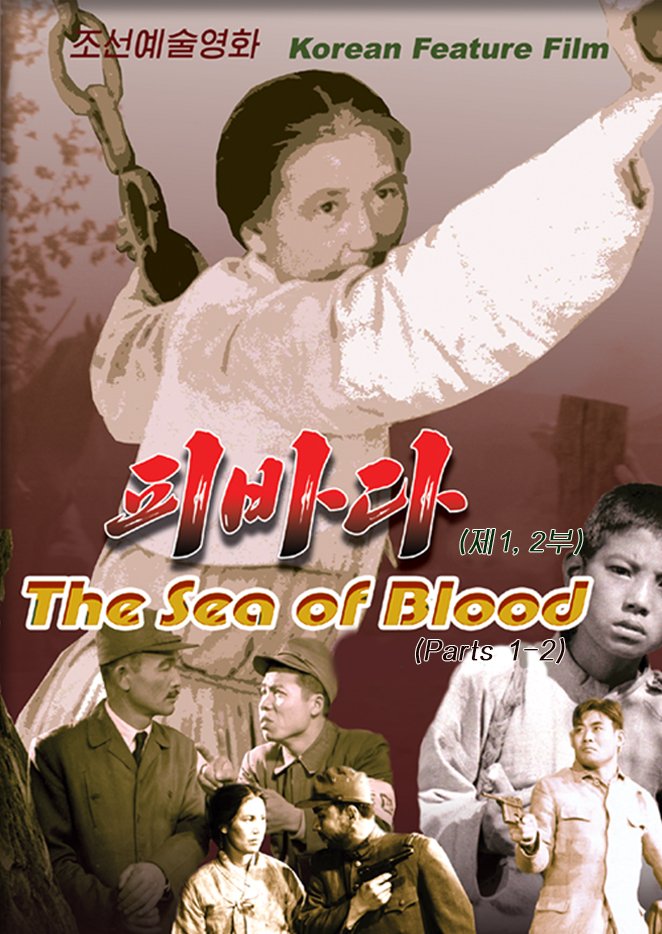

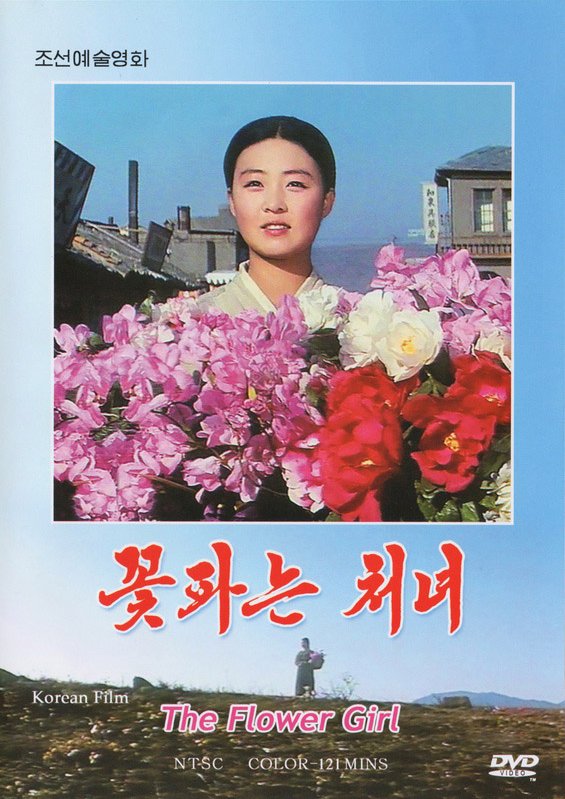

In consequence, he stepped in to get things done and, by stepping in, I mean literally giving on-the-spot guidance for members of cast and crew. Also, he sent directors and editors for training to the Soviet Union and encouraged screenwriters to seek inspiration even in Indian films… The results of his struggle materialized in such movies as Sea of Blood (a 5-hour-long war epic about a woman becoming a revolutionary fighter) and The Flower Girl (about the oppression of a poor girl in the heyday of Japanese colonialism). Both films, adaptations of revolutionary operas, received critical acclaim and even gained recognition overseas. However, Kim Jong Il wanted much more. He desired a genuine blockbuster and, in order to get it, he was determined to secure the services of the best South Korean director.

The Kidnapping of Shin Sang Ok and Choi Un Hee |

Shin Sang Ok was a South Korean filmmaker who started his career while working as an assistant on Viva Freedom! (1946). Learning from the best directors and buying his way into politics (making features to promote presidential candidates), Shin became a highly prosperous director, making everything from social realism to war flicks. He was married to a popular actress Choi Un Hee, but they divorced because of Shin’s affair. Eventually, the government revoked his working permit for the inclusion of erotic scenes in his productions. Also, his company fell in debt. This was his life until the kidnapping of Choi Un Hee.

The actress was lured into Hong Kong by false businessmen who offered her a film role. She was actually abducted and transported to North Korea in a cargo ship. She was kept in solitary confinement between 1978 and 1983 until Kim Jong Il invited her to a party where her ex-husband was present as well. It turned out that Shin went looking for Choi six months after her disappearance, but got abducted as well and thrown into prison. Cue 1983, Kim Jong Il, confident that the couple would not betray him, offered them to make new, blasting DPRK movies that will take the world by the storm. Shin and Choi complied, beginning the twisted, yet creative relationship with their captor.

|  |  |  |

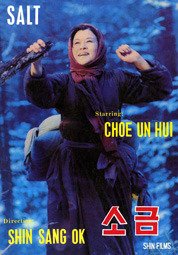

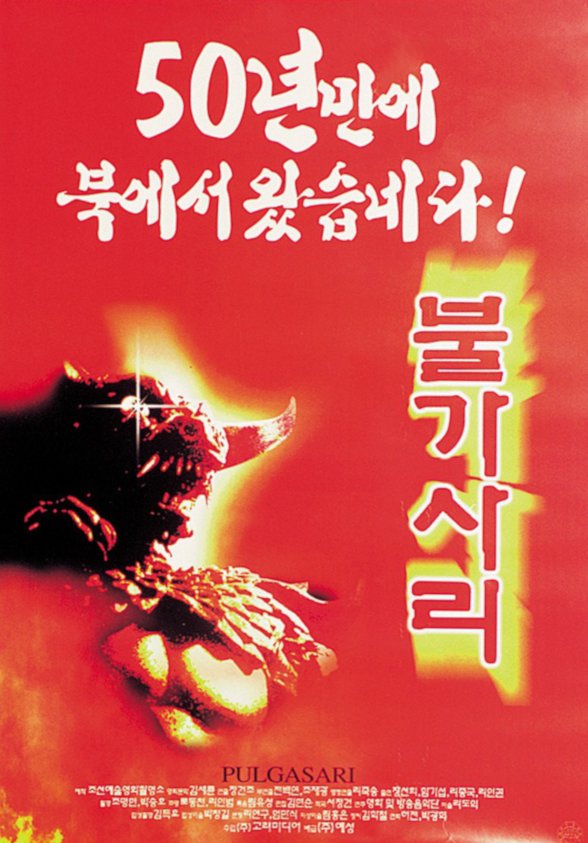

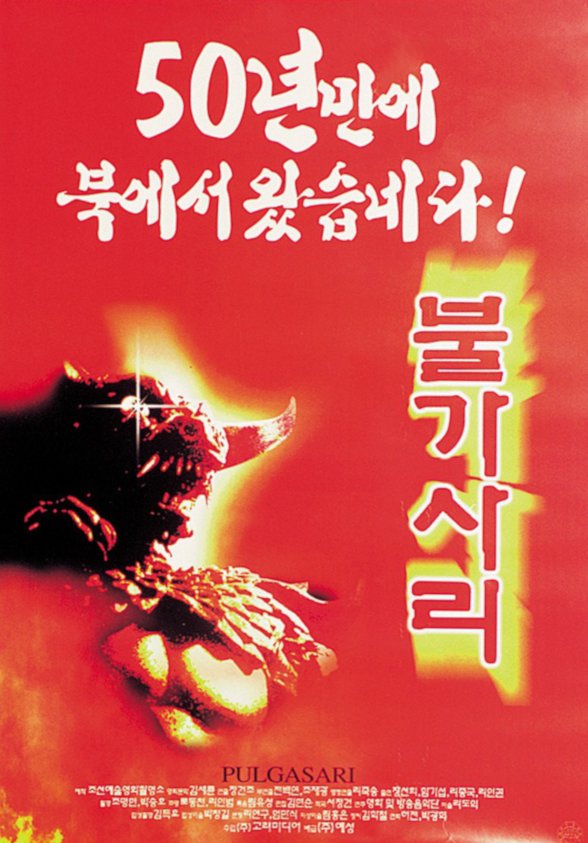

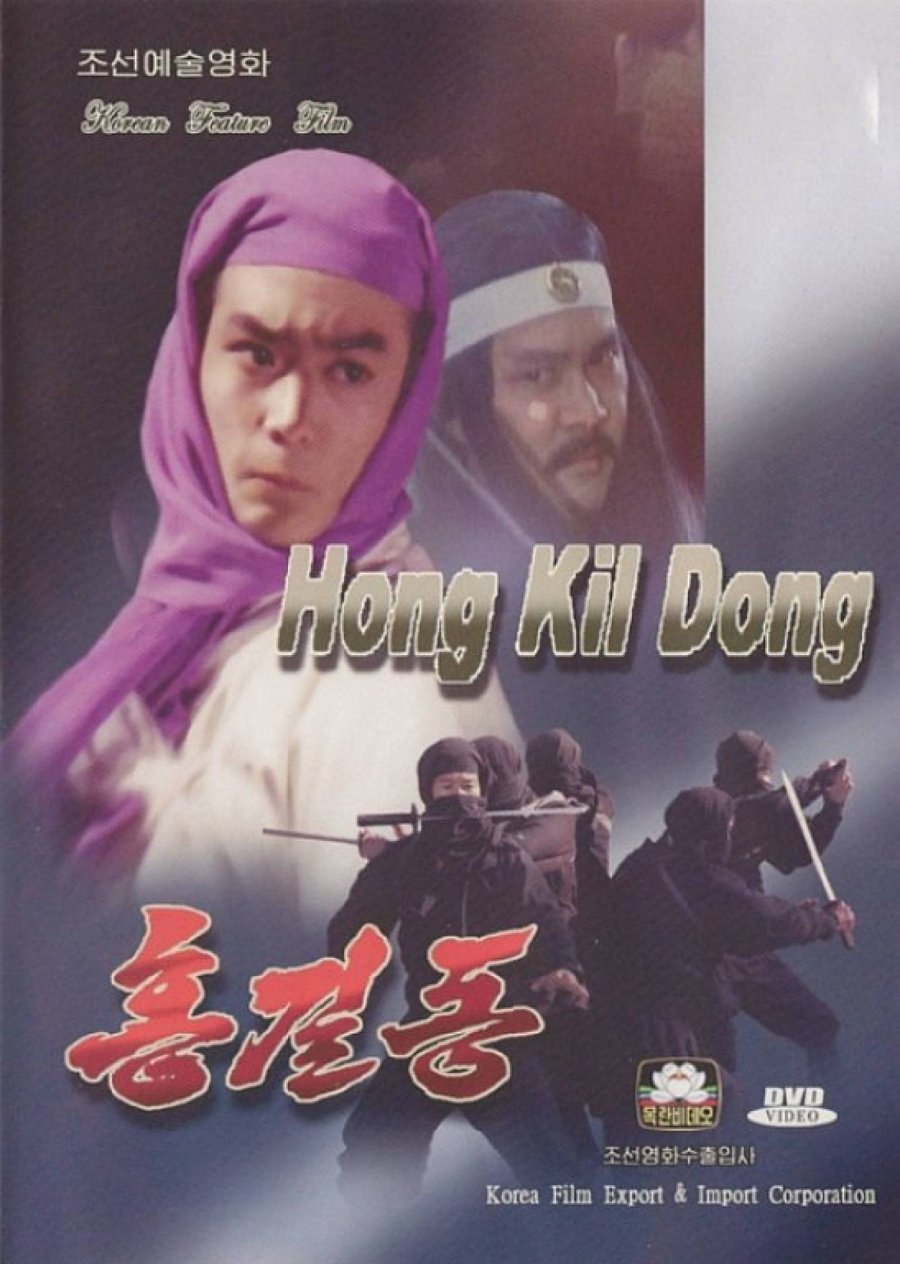

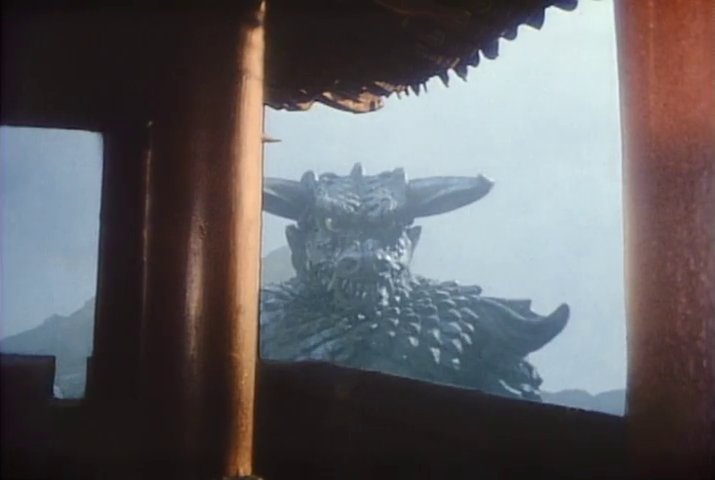

In the period between 1983 and 1986, the couple either directed, produced, or wrote 20(!) movies. The most popular flicks were the ones directed by Shin, and each of these marked a breakthrough for North Korean filmmaking. An Emissary of No Return featured a real European setting (Czechoslovakia) and Western actors. Love, Love, My Love was essentially a folk-tale love story which featured the first on-screen kiss. Runaway cleverly reinvented the standard Juche formula by emphasizing action (explosion of a real train at the end). Salt was a harrowing melodrama about a woman (played by Choi Un Hee) trying to save herself and her family by smuggling salt. The Tale of Shim Chong was co-produced in Austria, by the same crew that did the effects for The NeverEnding Story. Last but not least, Pulgasari was an over-the-top monster picture, which (allegedly) contains mockery of Kim Jong Il himself.

Shin and Choi were showered with glamour and gifts during their filmmaking frenzy. Nevertheless, the couple was afraid that they might soon become useless to Kim, so they secretly recorded conversations with him in order to have proof that they had not willingly defected to North Korea. Eventually, while negotiating a co-production deal in Vienna in 1986, they fled to the U.S. embassy and requested asylum. I do not know how their escape looked like, but it must have resembled the one from Doctor Stranger.

The Country I Saw |

“Can't you see how the Korean nation, forced to conclude the Ulsa 5-Point Treaty by our Japan a hundred years ago, has become a full-fledged nuclear power now; how it, confronting the US which you hold as God, made Korea a small but big country?” - Kayama Aiko

There are many outstanding North Korean films out there that would certainly deserve an article on their own, but none of them is as relevant today as the franchise The Country I Saw.

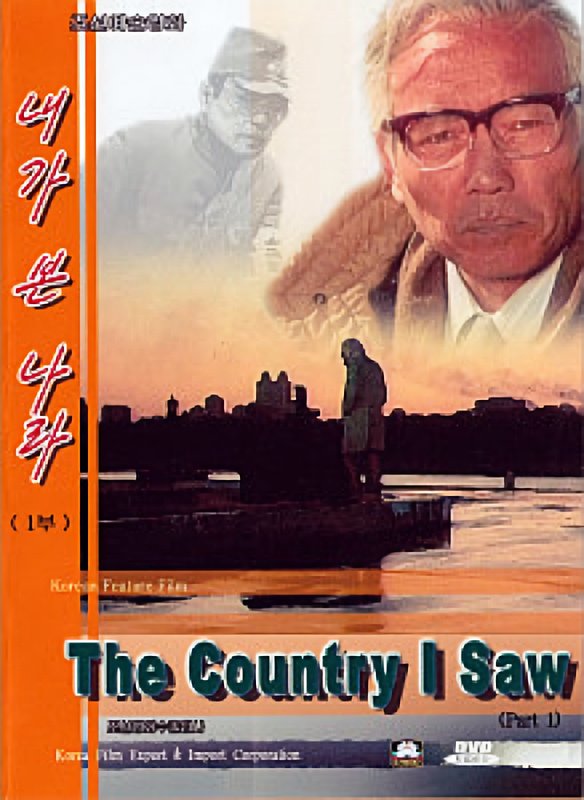

The first film of the franchise was released in 1988. It tells a typical North Korean story of the 1980s: a righteous foreigner who doubts the glory of North Korea decides to visit the country and observe things at first hand. Needless to say, the foreigner sees the spellbinding reality and changes his mind, vowing to support Kim Il Sung from now on.

The main character of the first film is Takahashi Minoru, a Japanese journalist who, after being challenged by a member of the public during a conference on the Juche system, resolves to go to North Korea and see the reality for himself. He is engrossed by the country’s economic development and superior social system as well as the benevolent character of President Kim Il Sung. He also meets some Koreans he wronged in the past while serving as a journalist for the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII, and begs for forgiveness, which is conceded to him when he finally acknowledges the true reality of the DPRK.

The movie was an instant domestic hit (in the way a movie can be a hit in North Korea), becoming one of the most notable films in the history of North Korean cinema. It was so successful that the Korean Film Studio decided to shoot two sequels 21 years later, and subsequently two more continuations.

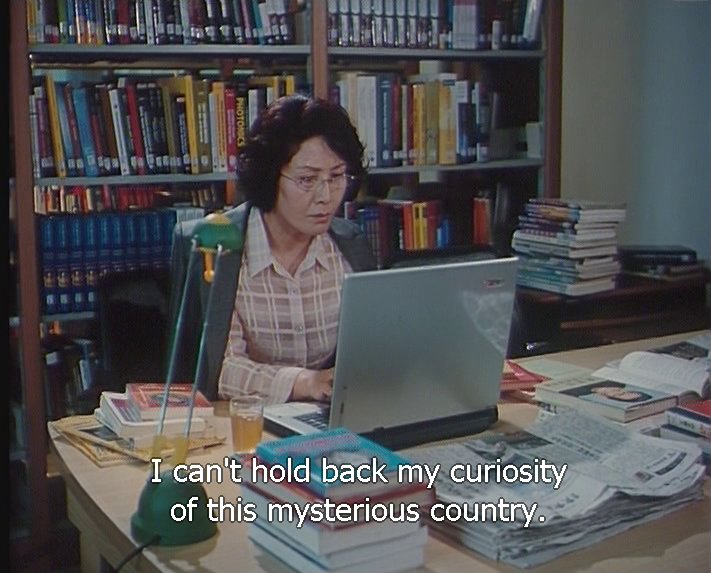

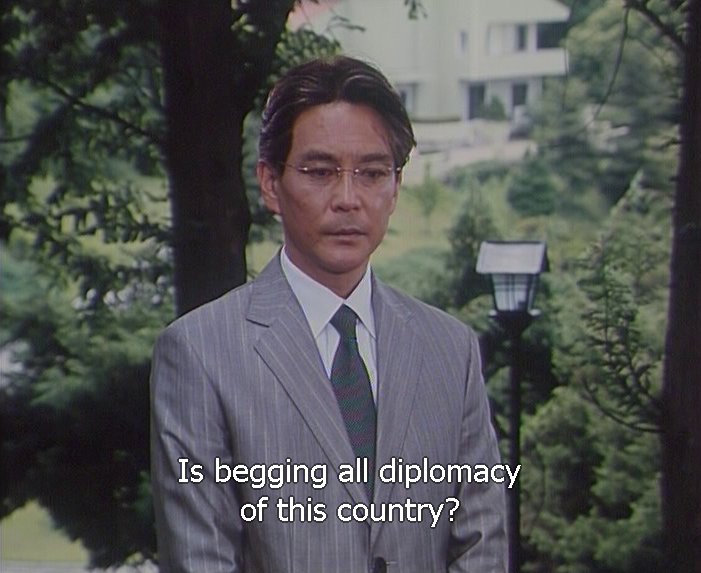

|  |

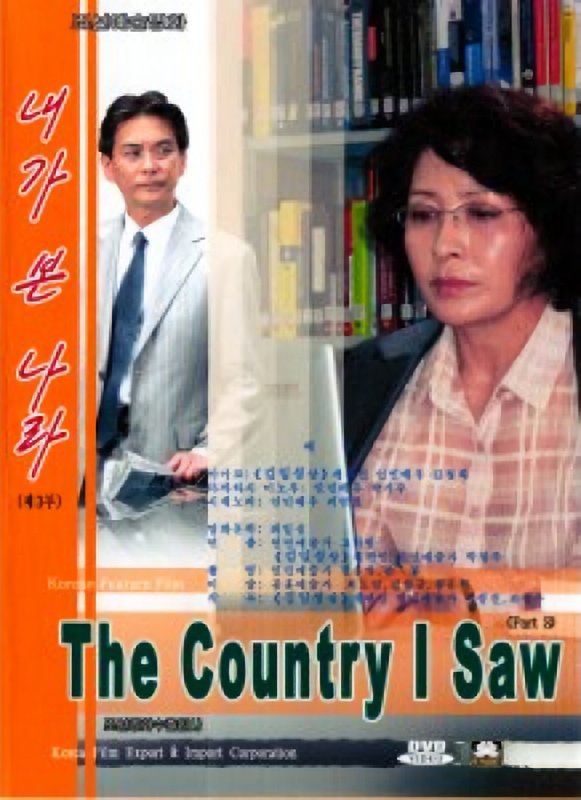

The Country I Saw 2 and the successive films follow Takahashi’s daughter, Kayama Aiko, an intellectual and strong-principled professor of International Politics at Tokyo University, who supports North Korea out of a sense of justice. She wants Japan to become a progressive country, just like North Korea, and is involved in pro-North Korea activism.

Her main adversary is Noda Shigenori, a patriotic Japanese diplomat and former student of Takahashi, whom he repudiated after the mentor wrote a book about his experiences in North Korea. Shigenori, following orders from the foreign minister, goes to great lengths to silence Aiko in order to save Japan from being ridiculed and embarrassed by the superiority of its former colonial subject.

While Shigenori loves his country and is loyal to it, he is disgruntled by its government, constantly putting Japan’s interests aside in favour of maintaining good relations with the US. This leads to the diplomat starting to question the real role of Japan in the international arena and its “hostile” policy towards North Korea, as well as what constitutes real patriotism.

|  |

“I thought I devoted my all to Japan. Why do I feel empty now?” - Noda Shigenori

The 'The Country I Saw' franchise is important because it is a propagandized depiction of how North Korea thinks the world perceives their actions and a window to understanding the rationale behind their pursuit of nuclear weapons. If there is one message The Country I Saw purports to convey, it is that nuclear weapons are not just the only guarantee for the survival of the DPRK, but also the source of its strength and the only way to be treated as an equal by the US. Policymakers should definitely draw some conclusions from these movies, which some analysts have even considered to be “predictive”.

The Country I Saw is recommended to anyone who has an interest in geopolitics, or simply wants to understand North Korea beyond the headlines. If you are a student of international relations, and Asia is one of your specialities or areas of interest, you should definitely check out these movies to gain some unique insights into the Hermit Kingdom’s foreign policy.

The Authors' Movie Recommendations |

| Pulgasari (1985) 불가사리 Korea in feudal times. An evil ruler ruthlessly oppresses his subjects. An old blacksmith in prison creates a tiny monster out of rice, which miraculously comes to life when it comes into contact with the blood of the blacksmith's daughter. Pulgasari becomes the defender of hard-working farmers, but the continuous hunger for iron becomes its damnation. |

| Hong Kil Dong (1986) 홍길동 Kil Dong, born of a concubine, is called “Flutist". He defends peasants from greedy rulers, as well as struggles for permission to marry a woman who derives from the high class. What fate is in store for him? The film was produced simultaneously with Pulgasari by Shin Sang Ok. |

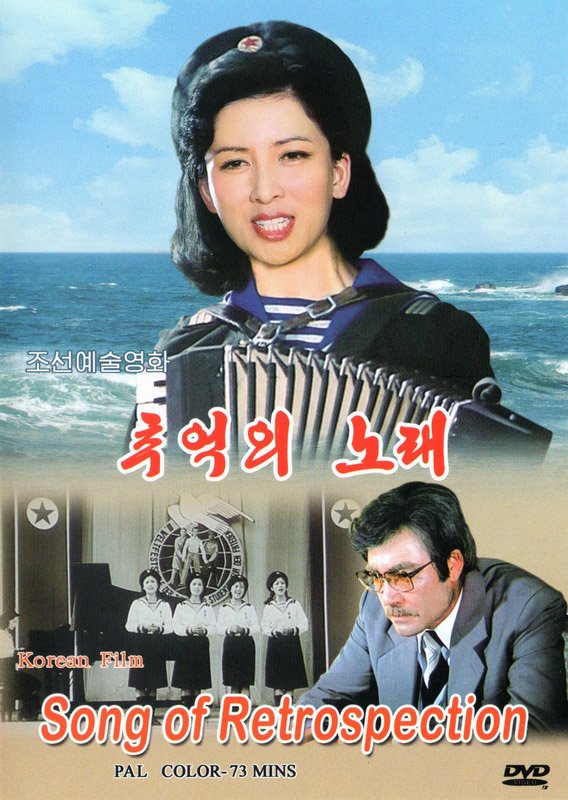

| Song of Retrospection (1986) 추억의 노래 Komak is a Western composer brought to Korea during the Korean War to write a sonata about the victory of the UN forces. He is then captured by North Korean forces led by Ra Sol Ju, who has a special talent for music. Komak witnesses the reality of North Korea and falls in love with her, who promises him she will give him her own composition as a gift when they meet again. 30 years later, Komak travels to North Korea, hoping to find her. |

| The Country I Saw (1988) 내가 본 나라 1부 While serving as a journalist for the Imperial Army of Japan, Takahashi Minoru sees first-hand the impact on Koreans who have had their national identity forcibly taken from them by the Japanese occupation of their country. Years later, he becomes a respected writer and, while giving a speech on the Juche system, has his perspective challenged by a young man in the auditorium. Having never seen North Korea, he realizes that, in order to meet his own standards of journalism, he must travel there and see for himself whether his opinion is valid or not. The Country I Saw Parts 2-5 (2009-) 내가 본 나라 2-5부 Kayama Aiko is a professor of International Politics at Tokyo University, and daughter of journalist Takahashi Minoru. She is a respected intellectual and strong-principled woman. Noda Shigenori is a patriotic Japanese diplomat. He is torn between his Japanese nationalism and his secret admiration of the DPRK as a strong, independent nuclear power. He works hard for his country, only for his efforts to be in vain due to his government kowtowing to the US. They cross paths as they witness the superiority of the DPRK and its social system amid the country’s recent nuclear achievements. |

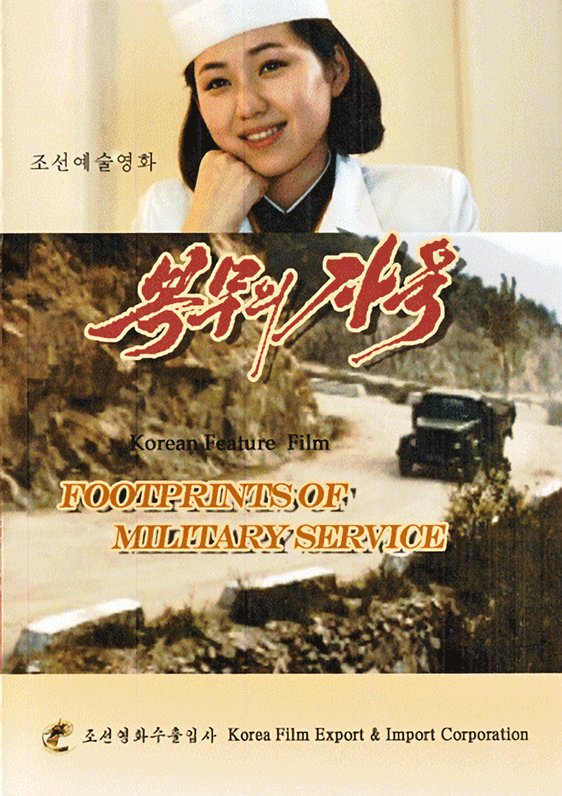

| Footprints of Military Service (2014) 복무의 자욱 Choe Seong Min is a battalion commander devoted to the maintenance of trucks in a remote army base in the mountains. One day, on the road, he comes across a stranded female medical unit led by beautiful Song Yu Jeong, with whom he has a special connection he is not yet aware of. He falls for her at first sight, and from now own will devote himself to pursue her. Will his love be reciprocated? |

| The Story of Our Home (2016) 우리 집 이야기 Ri Jong A is an 18-year-old girl who has just finished senior middle school when she decides to look after the neighbour’s orphaned children. She gives them love as much as she can and makes every effort to make their dreams come true. Taking care of them, she learns and grows as a person. The Story of Our Home received the Best Film award at the 15th Pyongyang International Film Festival in 2016. The main actress, Paek Sol Mi, received the Best Actress of Feature Film award. |

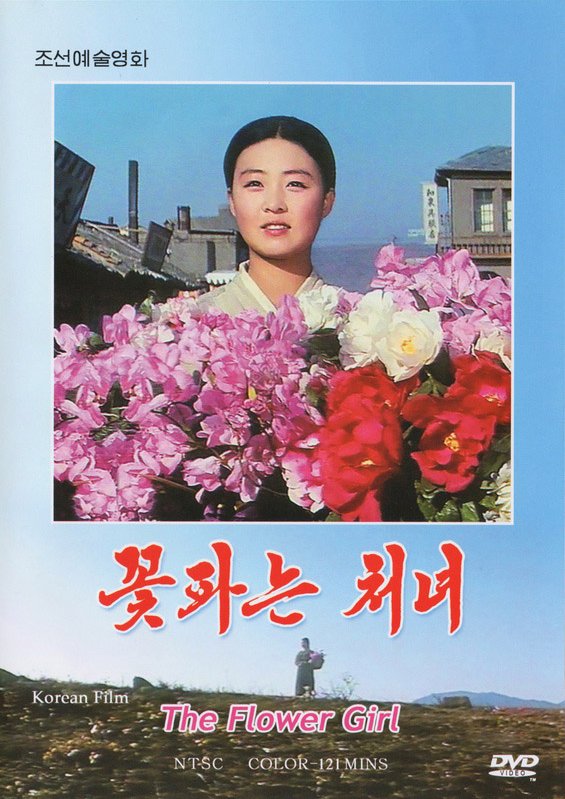

| The Flower Girl (1972) 꽃파는 처녀 Set in the 1930s, the film tells the story of a poor, rural girl who sells flowers every day in order to support her family. The Flower Girl suffers many hardships from ruthless Japanese oppressors, but there is still hope for salvation. The first North Korean film to win an international film award (at the 18th Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 1972). For her role in the film, actress Hong Yong Hee was depicted on the North Korean one won banknote. |

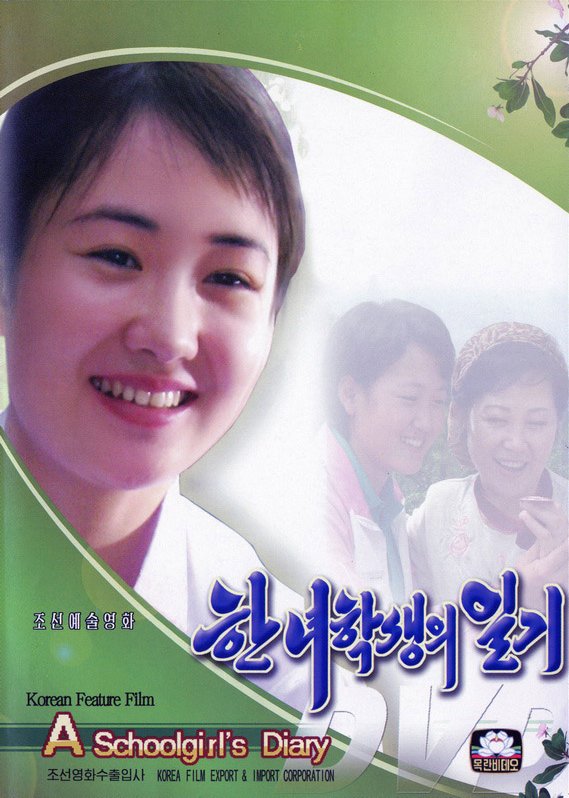

| The Schoolgirl's Diary (2007) 한 녀학생의 일기 A young student defies her father when she sees no point in his exhausting work. The father is a computer engineer working in a distant town, whereas her mother is a librarian who relentlessly translates scientific articles for the absent husband. The daughter takes it upon herself to take care of the family. Since 2016, the movie is, allegedly, banned in North Korea for the too accurate depiction of North Korean reality. |

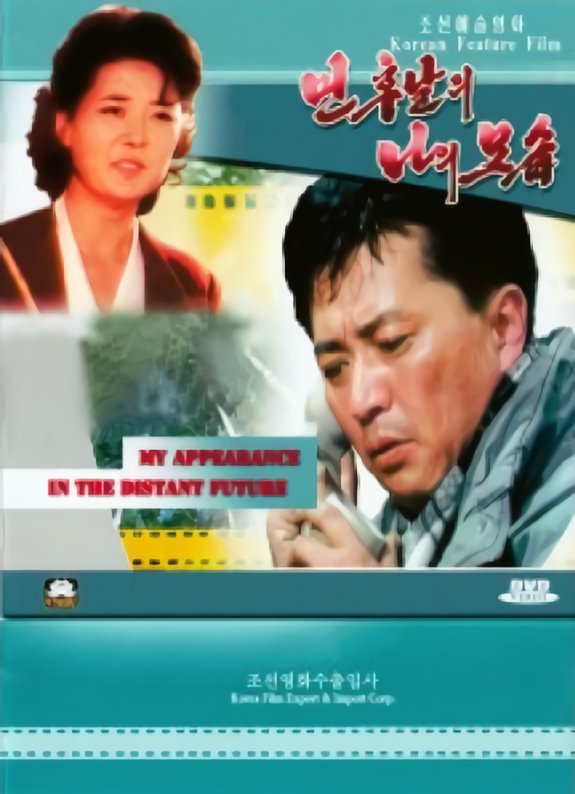

| Myself in the Distant Future (1997) 먼 후날의 나의 모습 The son of a respected architect is a carefree taxi driver who does not believe in the ideas of revolutionary struggle and self-devotion to the country. His attitude changes when he meets a beautiful girl who happens to be the leader of a shock brigade of plasterers. In order to win her over, he attempts to become an exemplary North Korean worker. The protagonist learns that there is more to life than just consumerist pleasures. Everyone should be happy in their place of birth, regardless of the fact that it is a city or the countryside. |

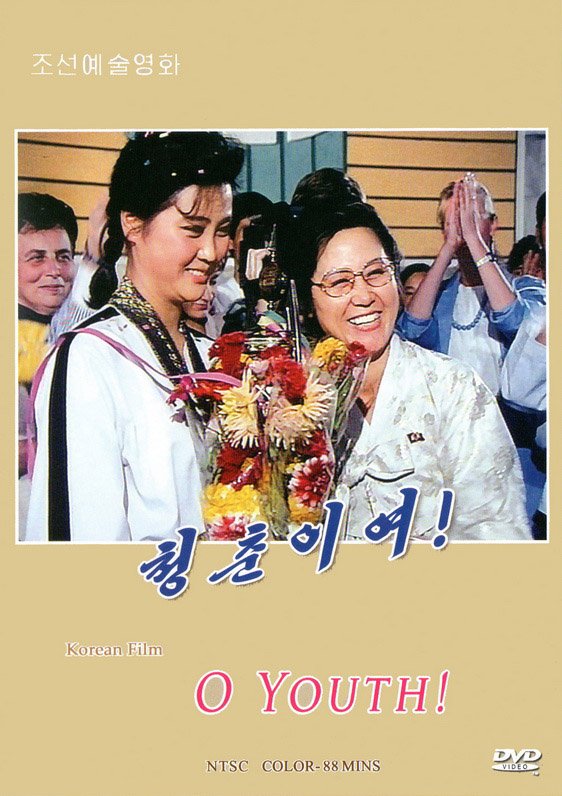

| O Youth! (1994) 청춘이여 Ki Ho is a historian who is engrossed only in his research and has no intention to marry even though he is already 30. His mother is anxious to get him married as soon as possible, while each of his five sisters introduces him to a girl. Will Ki Ho find the one? |

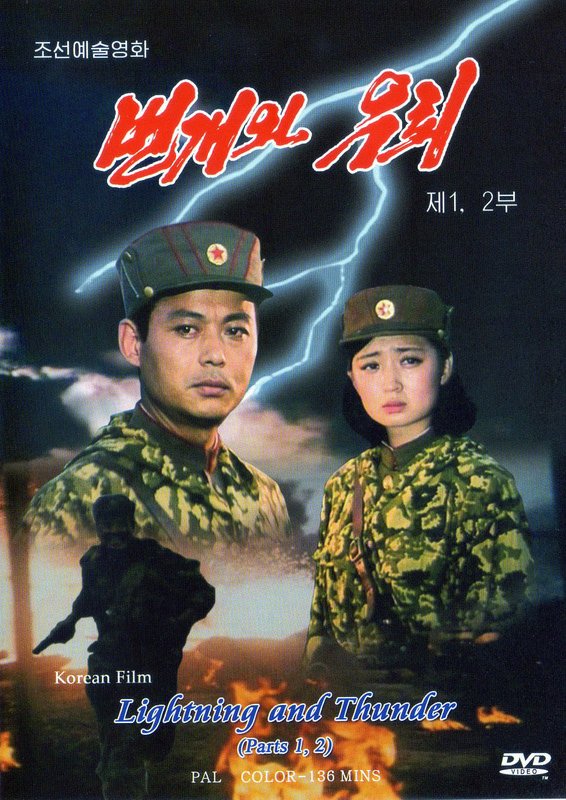

| Lightning and Thunder (1986) 번개와 우뢰 South Korean special forces are planning to infiltrate North Korea to blow up an air force base to shake the country's aerial defense capabilities. North Korean special forces infiltrate the South Korean army base disguised as South Korean soldiers to thwart the attack. Will their mission succeed? And will they make home safely? |

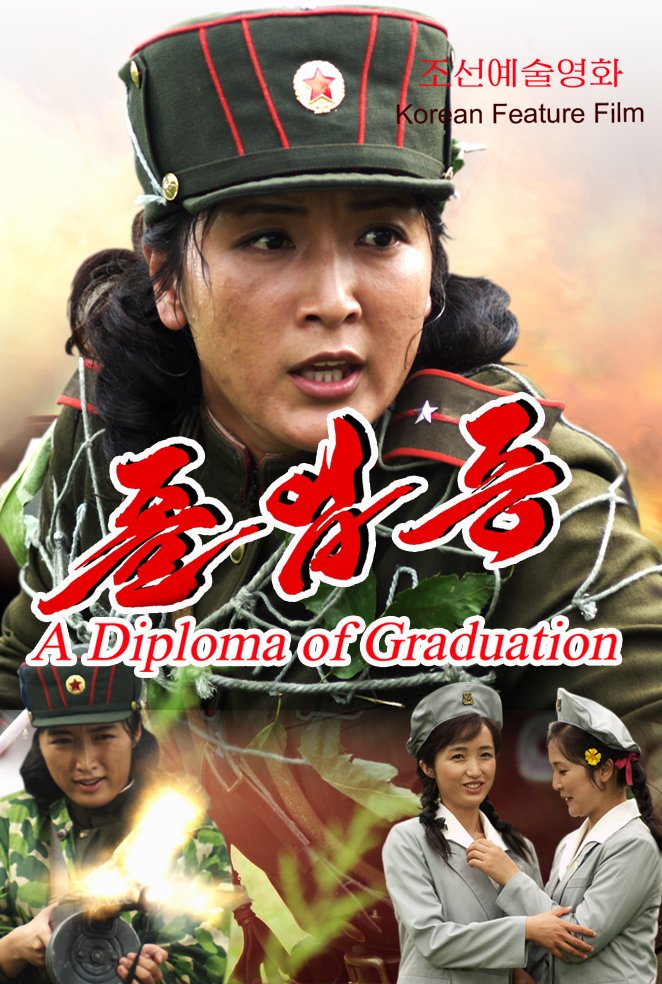

| A Diploma of Graduation (2016) 졸업증 It's the year 1950. A group of students receive their diplomas from Kim Il Sung University. All of a sudden, the Korean War breaks out, and they leave their families to enlist in the recently created Korean People's Army. How will the horrors of war change them? Will they survive? |

What happened to them? |

|

|

Selected Trivia |

|

|

As the Dear Leader once wrote in his book On the Art of Cinema: “The art of filming deals with a world of infinite breadth and diversity. There is nothing in society and nature, in human life or the physical world, which cannot be captured by the camera.”

Indeed, North Korean dramas and movies may be filled with ideology and propaganda, but that does not mean that these are lesser works of art. These pictures still manage to convey emotions by telling stories of hardships, redemption, and devotion to the country. Just as the heroine of Salt triumphantly carries her burden into the wild, North Korea still has not said the last word in terms of moviemaking. Who knows? Maybe their greatest masterpiece is yet to be produced…

In the meantime, we should enjoy the dramas and films that this country has to offer. If not for historical reasons, then at least to appreciate the social realist aesthetics.

*Footnote: In 1992, the year The Nation and Destiny started airing, North Korean propaganda started telling citizens that eating three meals a day was excessive, in anticipation of the Arduous March (famine). The Nation and Destiny was aired before, during, and after the Arduous March.

Sources: The North Korean Films of Shing Sang Ok * North Korea Handbook * Kim Jong Il & Hollywood: A Tale of Kidnapping, Videotapes and Sean Connery * The Lovers and the Despot (documentary) * North Korean Film Madness (documentary) * North Korea: Mass Games Performance 2018 * Kim Jong Il: On the Art of Cinema * A Kim Jong Il Production: The Extraordinary True Story of a Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, and a Young Dictator's Rise to Power (by Paul Fisher) * North Korea Bans Formerly Approved Films Now Deemed Sensitive * Tatiana Gabroussenko's editorials about NK movies and dramas * North Korea's Cinema of Dreams (documentary)